This story was originally published by Honolulu Civil Beat and is republished with permission.

More than 140 insurance industry plaintiffs have joined the cascade of lawsuits filed against utilities and landowners related to the Maui wildfires, a move that could set up a battle over resources available to pay victims of the disaster that killed 100 people and destroyed much of Lahaina in August.

The global insurance industry has swept into Honolulu state court, seeking to collect reimbursements for claims paid to policyholders. Those total more than $1 billion in West Maui for residential property alone, according to the latest data from the Insurance Division of the Hawaiʻi Department of Commerce and Consumer Affairs.

The plaintiffs include names familiar to Hawaiʻi homeowners: insurers like State Farm Fire and Casualty Co., USAA Casualty Insurance Co., Island Insurance and Tradewind Insurance.

Also included are scores of additional companies, such as the French and Australian branches of the giant Swiss Re, Japan’s Mitsui Sumimoto Insurance, and Lloyd’s, the London-based marketplace known for insuring everything from ship cargo, fine art and space satellites to Bruce Springsteen’s voice.

Defendants include Hawaiian Electric, Hawaiian Telcom, Kamehameha Schools and other unnamed parties the insurers allege were negligent in allowing the fires to start and spread.

It’s a predictable turn of events, says Robert Anderson, director of the Center for Risk Management Research at the University of California, Berkeley.

When a company like State Farm issues a policy to a homeowner, Anderson said in an email, State Farm typically buys reinsurance from another company like Swiss Re to cover the risk from catastrophic events, such as a hurricane hitting an urban area “or a wildfire that spreads and takes out a large number of homes, as happened in Lahaina.”

When such a catastrophe occurs, State Farm would typically pay claims to the insured property owners and get reimbursed by its reinsurers, Anderson said.

If the losses occurred because of negligence, the insurer and reinsurers can sue the negligent parties to recover the payments “in the same way that a health insurance company could seek to recover the costs of treating someone injured in an automobile accident,” he said.

Multiply that by thousands of claims, and it explains the enormous number of insurance company plaintiffs, spread out over 26 states and a half dozen countries, filing suit in Hawaiʻi. It’s also a sign that the global insurance market is functioning adequately to spread the risk of a major catastrophe in Hawaiʻi, said Sumner LaCroix, an economist with the University of Hawaiʻi Economic Research Organization.

“The last thing we want in Hawaiʻi is to find out that two or three companies bear the risk of having a hurricane hit Hawaiʻi,” LaCroix said.

Battle could ensue between victims and insurers

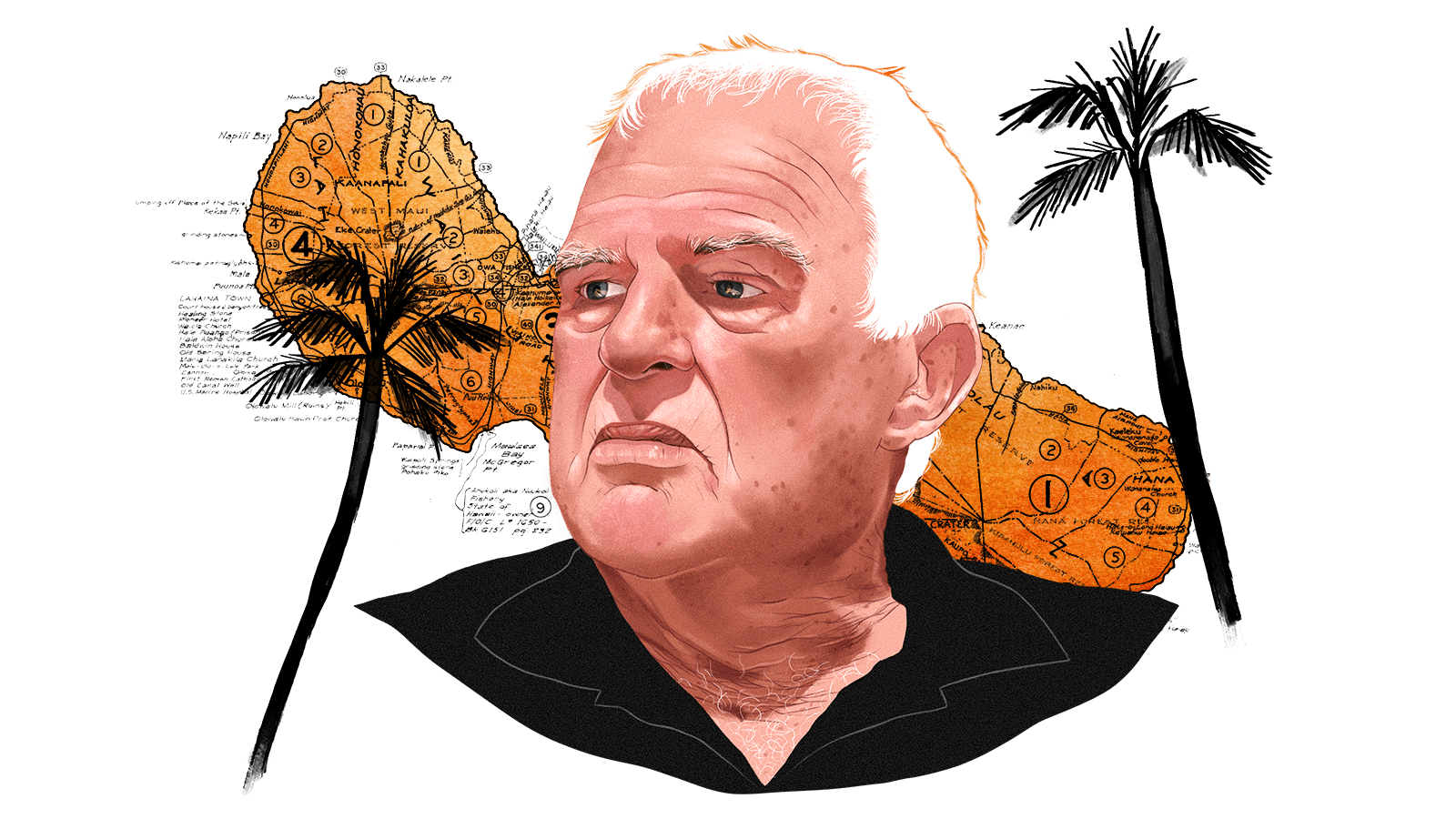

The suit could have major implications in the long run for plaintiffs seeking to recover claims for damages from Hawaiian Electric and the others, said Mark Davis, a Honolulu trial lawyer who is serving as a liaison for dozens of plaintiffs lawyers who have filed suits on behalf of victims in Maui court.

At this point, Davis said, the insurance companies and other plaintiffs have a common goal: to prove that the utilities or landowners or both acted negligently in allowing the fires to start and spread. The insurance industry has had its own teams of investigators, Davis said.

“For the most part their inquiries go hand in hand with the plaintiffs’ inquiries,” he said.

Indeed, the insurance industry’s factual allegations of what happened on Aug. 8 mirror the allegations in many of the negligence suits filed by residents.

But eventually, Davis said, Lahaina residents will find themselves competing with the insurance companies for the same pot of money.

To the extent that the insurers have paid claims, they’ll likely try to assert priority over the homeowners, which happened after lawsuits related to California wildfires drove Pacific Gas & Electric Co. into bankruptcy in 2019, Davis said.

Still some states have adopted a legal principle known as the “made whole doctrine,” which means insurers can’t jump the line ahead of insured property owners until the insured property owners’ damages are completely covered. Otherwise, a property owner could collect from both their insurance company and the wrongdoer if negligence is proven. All of this sets the stage for a fight between the individual plaintiffs and the insurers if they can prove the utilities or landowners were negligent.

“Inevitably, that is a big struggle later on as they start to dole out resources,” Davis said.

Hawaiian Electric and Hawaiian Telcom declined to comment. Paul Alston, an attorney for Kamehameha Schools trustees also declined to comment. Lawyers for the insurance companies did not return calls.

Hawaiian Electric, meanwhile, does not have the resources to reimburse the property insurers for the massive claims paid out so far, if the insurers were to prevail in their suit. The company’s stock price has plummeted since the fires. Rating agencies have slashed Hawaiian Electric’s bond rating, meaning it will cost more for the company to borrow money. And Hawaiian Electric has largely tapped out its lines of credit to raise cash.

The company is pursuing federal grant funds, which it hopes to steer to rebuilding infrastructure, but that money can’t be used to pay damages. Meanwhile, a big chunk of proceeds from a woefully inadequate insurance policy, worth $165 million, that could be used to reimburse the insurers has already been pledged to a settlement fund for people killed and injured in the fires.

The company has promised $75 million to the so-called Maui Recovery Fund. Makana McClellan, a spokesman for Gov. Josh Green, said the fund expects to have $175 million total when it becomes operational on March 1. Green previously announced the state, Kamehameha Schools and Maui County also would provide funding. McClellan said more details would be available this week.

Each victim could receive more than $1 million from the fund if they choose to drop their legal claims, Green has said.

But the fund is not meant to address property damage. And how much money will be available to cover such claims isn’t clear. After putting $75 million in the recovery fund, the company theoretically would have $90 million. But Hawaiian Electric has been bleeding cash on lawyers.

When the company held its quarterly earnings call for the period ended Sept. 30, Hawaiian Electric revealed it had spent $27.6 million on fire-related expenses to that point, including $10.8 million – or about $1.5 million a week – on legal fees. And that was as the lawsuits had just begun pouring in. It remains to be seen how much Hawaiian Electric’s lawyers have cannibalized the company’s liability insurance at this point, 24 weeks after the fire.

Meanwhile, the staggering amount of insurance losses is becoming clear. According to the Hawaiʻi Insurance Division, as of Nov. 30, insurers reported 3,947 claims for residential property in West Maui, including 1,689 total losses. Estimated losses totaled $1.54 billion, of which insurers had paid $1.09 billion.

Perhaps the only good news in all of this, Davis said, is that insurance companies don’t appear to be squabbling about paying claims, which he said isn’t surprising given that so many homes were completely burned.

“There’s not a lot to talk about if you bought ‘x’ amount of insurance and your house is dust,” he said.

Civil Beat’s coverage of Maui County is supported in part by grants from the Nuestro Futuro Foundation.